Inflation: Here To Stay, Or Just Passing Through?

As we begin the second half of 2021, vaccination rates are rising, businesses and economics continue to reopen, and the word on the street is “inflation.” Yup. Inflation is back, but for how long? Economists disagree on that prognosis and exploring the arguments on both sides is the subject of our discussion this quarter.

Those of us who were alive during the 1970s may remember this image. You may even have donned one of these buttons while you waited in long lines to fill up your car’s gas tank. The decade of the ‘70s had many high points: the end of the Vietnam war, the opening of Walt Disney World in Florida, the US Bicentennial, and most notably, the founding of Towneley Capital Management. Economically, however, the decade was a disaster.

Defying Keynesian economic theory prevalent at the time, high unemployment, high inflation, and slow GDP growth came together during the 1970s to create a perfect storm called “stagflation.” It wasn't until 1979, when Fed Chairman, Paul Volcker, shifted the Fed’s focus from Keynes’ fiscal policies to Milton Friedman’s monetarist policies (founded on the Nobel Prize-winning economist’s theory that prices cannot increase without an increase in the money supply) that we were finally able to “Whip Inflation Now.” The lessons learned from that period 50 years ago should serve us well if we indeed find ourselves on the precipice of another bout with sustained price inflation.

Inflation Rates are Rising

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U, aka “headline inflation”) rose 0.9% in June on a seasonally adjusted basis after rising 0.6% in May. Over the past 12 months, headline inflation is up 5.4%, before seasonal adjustment, the largest 12-month increase since August 2008. The CPI-U has been trending up every month since January, when the 12-month change was 1.4%. Excluding the volatile food and energy sectors, core CPI rose 4.5% over the past 12-months through June, its largest increase since November 1991.

June’s inflation increase exceeded all forecasts and challenges the Fed’s allegiance to its current easy money policy. Economists disagree about whether inflation’s recent upward trajectory signals the beginning of prolonged price inflation, as during the 1970s, or is merely transitory, resulting from temporary shortages and pent-up demand. We believe that both arguments have merit.

Argument #1: Higher Price Inflation is Here to Stay

Some who claim we are entering a period of prolonged price inflation believe that inflation is a monetary phenomenon, as Milton Friedman once said, and that the Fed’s policy of monetizing the national debt will ultimately lead to substantially higher prices. If the Fed continues to print money as it has, we believe this is possible, although unlikely. Those in this camp draw comparisons to the soaring inflation and unemployment of the 1970s that kept a lid on economic growth and spawned two recessions during the 1980s that financially devastated millions of people.

The Great Inflation

The 1973 OPEC oil embargo that caused worldwide gasoline shortages is often blamed for the inflation that encapsulated the US and much of the world during the 1970s. However, the Great Inflation began in 1965 and lasted until 1983. The real culprits were the Federal Reserve’s policies that allowed for excessive growth in the money supply, along with then-president Nixon’s attempts to reduce unemployment and shore up the value of the US dollar before the 1972 election.

Nixon’s executive order freezing wages and prices set the stage for a decade of high inflation and unemployment. Moreover, by breaking gold’s link to the U.S. dollar and ending the world’s ability to convert gold into dollars, Nixon effectively killed the Bretton Woods arrangement and the fixed exchange rate system. As a result, although Nixon won reelection in 1972 by a landslide, his constituents would soon suffer from years of soaring inflation and unemployment wrought by his administration’s misguided policies. In his 1994 book, Stocks for the Long Run: A Guide for Long Term Growth, Wharton professor, Jeremy Siegel, deemed the Great Inflation “the greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the postwar period.”

Those who claim we are at the forefront of another Great Inflation draw parallels between the Nixon-era monetary policies and the present-day Fed’s easy money policies, including the relatively recent rise in the money supply. Due to its quantitative easing measures, the current Fed’s recent expansion of the monetary base (currency in circulation and bank deposits) has raised concerns about high inflation. Moreover, critics argue that by flooding the economy with massive amounts of liquidity, the Fed may have set the stage for future price surges.

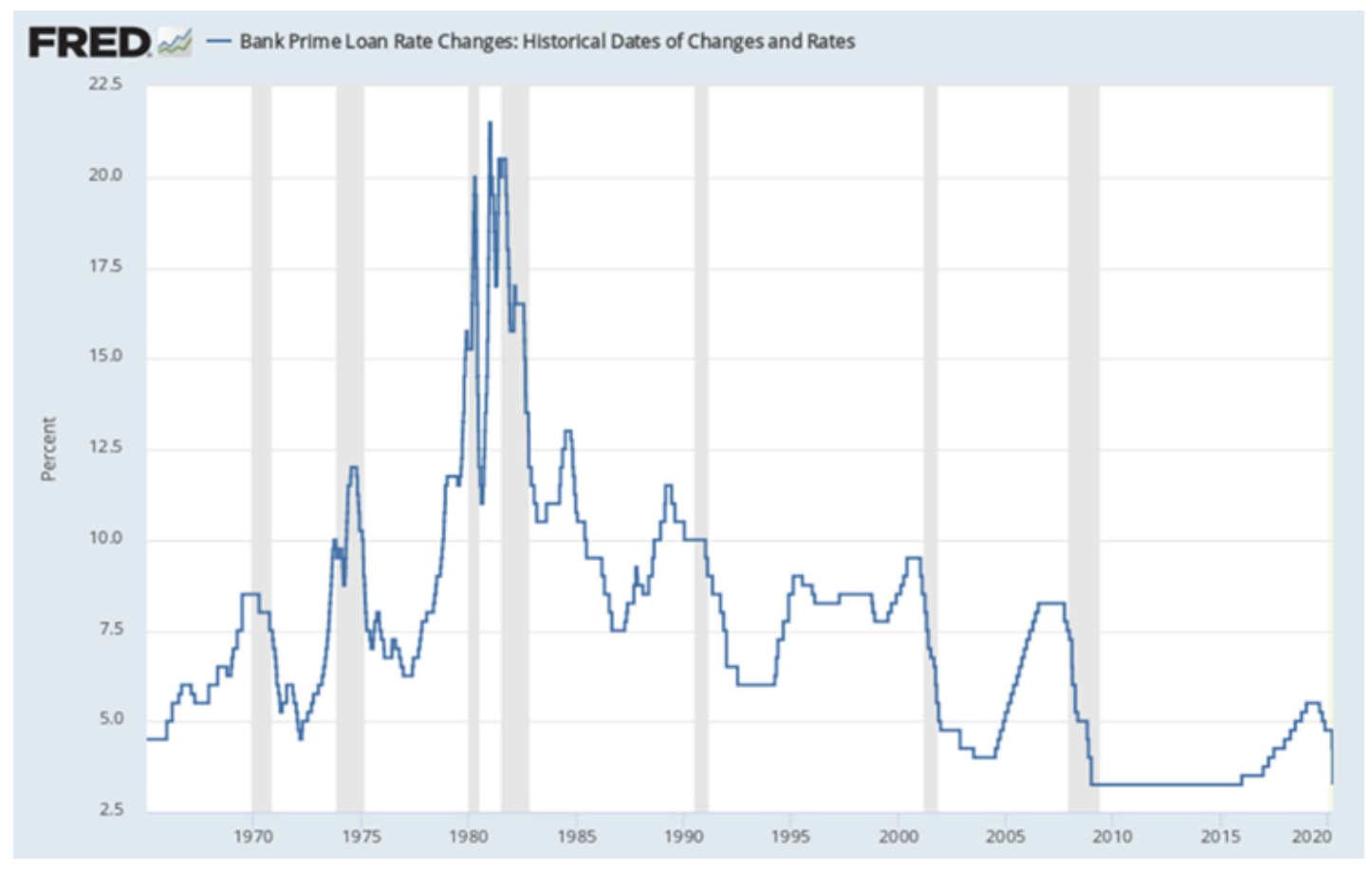

Paul Volcker to the Rescue

The soaring inflation that battered the US economy in the 1970s finally ended after the Fed, led by Chairman Paul Volcker in 1979, applied contractionary monetary policy to rein in inflation. Volcker’s Fed slowed the rate of growth of the money supply and raised interest rates. As a result, the federal funds rate, which was just below 11% in 1979, rose to 20% by June 1981. Moreover, the prime interest rate, which determines consumer loan rates, reached 21.5% in June 1982. Though painful to endure, by 1983, Volcker’s bold action had returned the inflation rate and inflation expectations to their previously low and stable levels.

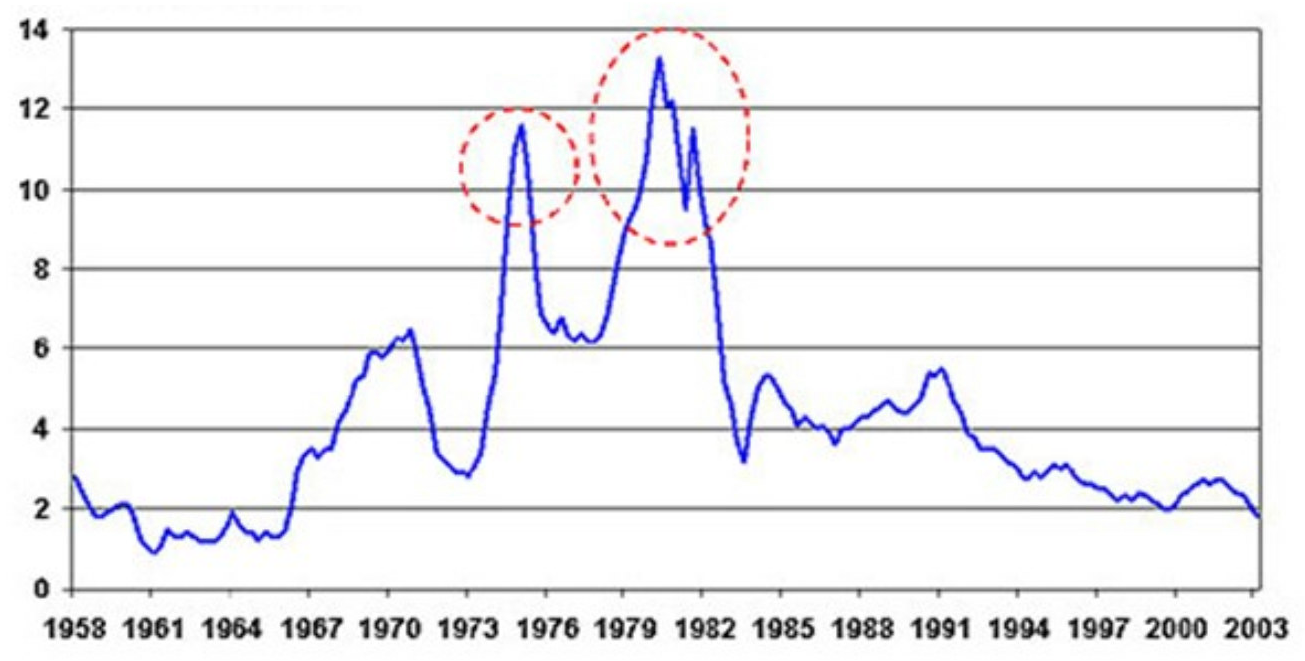

Inflation Soared in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s

Core Consumer Price Index (Less Food and Energy Expenditures)

(Percent Change, year-over-year)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, current as of June 2003.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.)

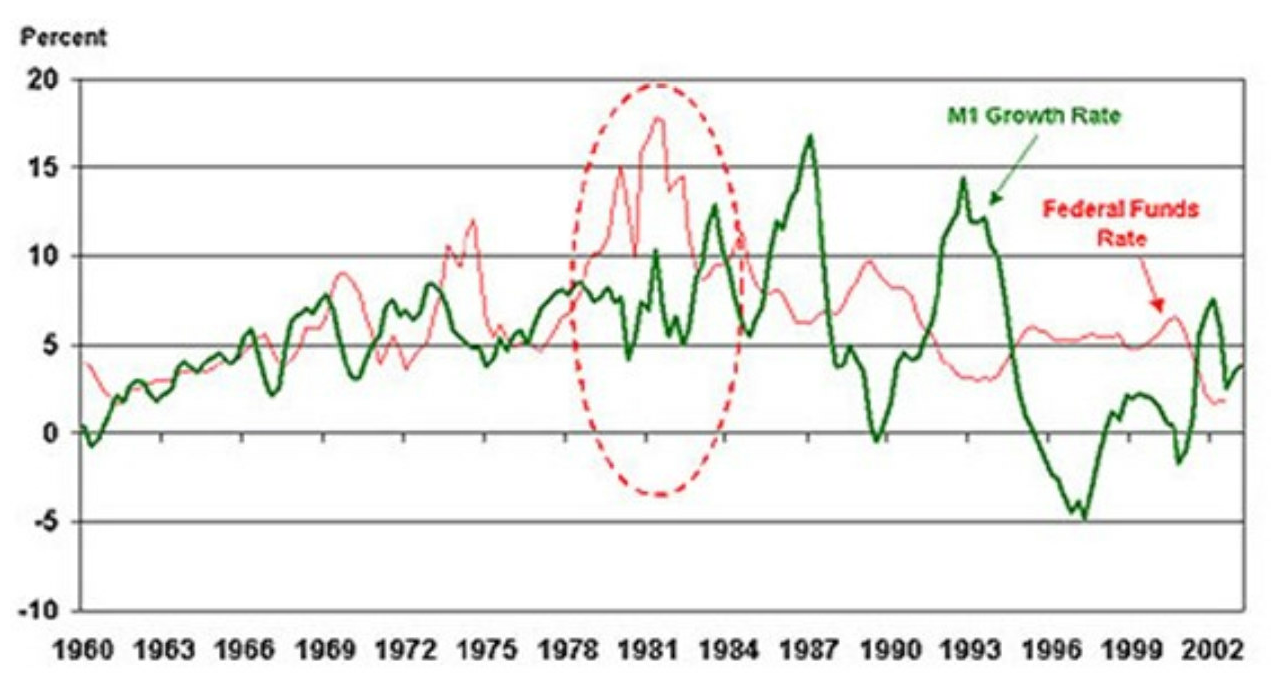

Before October 1979, the Federal Reserve carried out its mandate primarily by targeting the price of federal bank reserves, which is gauged by changes in the federal funds rate, the interest rate that banks charge for borrowing from each other overnight. Once the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) set the federal funds target rate, the Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York bought and sold government securities to achieve the target rate. Chairman Volcker changed the FOMC’s approach to monetary policy to target the quantity of money, specifically nonborrowed reserves. Although more helpful in controlling inflation, the Fed’s change in direction caused greater volatility in the federal funds rate between 1979 and 1982.

The Federal Funds Rate and the M1 Growth Rate Remained Volatile in the 1979-1982 Period

Source: Federal Reserve Board, current as of June 2003.

Lessons Learned from the 1970s

The lessons we learned from the Great Inflation period will hopefully keep us from repeating our mistakes. First, price stability is vitally important to economic welfare. During the 1970s, the Fed’s policy was to tolerate high price inflation to stimulate the economy. In 1996, Fed policymakers privately agreed that their target for inflation was 2%, but, at Chairman Greenspan's insistence, this was not announced publicly. In January 2012, furthering the Fed’s relatively new policy of transparency, the Fed released its “Statement on Longer Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy”. The statement explained the Fed’s longer-run goals and its strategy for setting monetary policy to achieve them and, for the first time, established a numerical longer-run goal for inflation:

“In the Committee’s judgment, an annual rate of increase of 2 percent in the price index for personal consumption expenditures—an important price measure for consumer spending on goods and services—is most consistent, over the longer run, with meeting the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate to promote both maximum employment and price stability.”

The Fed reaffirms its longer-run goals in a similar statement issued annually during each January meeting.

The second lesson we learned is that maintaining the public’s confidence in the Fed’s ability to moderate inflation is crucial. The Fed’s lukewarm policy responses and lack of transparency during the 1970s, caused people to lose faith in the Fed’s ability to keep inflation in check. Consequently, they came to believe that high inflation was permanent. Business owners set their prices based on that belief, so high inflation essentially became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Chairman Volcker and the Fed’s tough medicine approach to fighting inflation, along with a new commitment to publicly disclosing Fed actions and intentions, earned the public’s trust over time and encouraged people to expect lower and less volatile inflation in the future.

Argument #2: Current Price Inflation Is Transitory

The opposing argument that the current price inflation coming out of the pandemic is transitory also has merit. It assumes that supply disruptions are primarily the result of the COVID-19 shutdown and will resolve themselves over the next 6-12 months. In addition, base effects are creating a false impression that inflation is rising. A related assumption is that current levels of unemployment are artificially high as unemployment benefits, particularly the $300 per week federal subsidy, are discouraging some people from returning to work. Once the subsidy ends, some argue, more people will return to the workforce. The opposing argument that the current price inflation coming out of the pandemic is transitory also has merit. It assumes that supply disruptions are primarily the result of the COVID-19 shutdown and will resolve themselves over the next 6-12 months. In addition, base effects are creating a false impression that inflation is rising. A related assumption is that current levels of unemployment are artificially high as unemployment benefits, particularly the $300 per week federal subsidy, are discouraging some people from returning to work. Once the subsidy ends, some argue, more people will return to the workforce.

We already see signs that higher prices for raw materials and supply chain intermediate goods are receding. For example, the costs of both new and used cars were up sharply due to a shortage of semiconductor chips. However, with solid profit incentives to continue boosting supply, car prices are expected to normalize over time but may take several more months. Likewise, after little to no demand for travel during 2020, the airline and hotel industries face surging demand as the global economy reopens. Eighty percent of the increase in core inflation (CPI) is due to industries experiencing transitory issues. Economists in the transitory inflation camp expect prices in these industries to decline further during the second half of this year.

Recent reports of rising inflation are also somewhat misleading. We measure inflation as a change in the Consumer Price Index over months, usually twelve. Twelve months ago, we were amid a lockdown due to COVID-19. As a result, many businesses were closed or operating at minimal capacity. To cut costs, manufacturers slowed or even stopped production, which impacted suppliers as well as consumers. As a result, the Spring 2020 CPI data compared to 2019 reflected deflation. This year, comparing changes in CPI to 2020’s meager numbers has artificially boosted inflation. These so-called “base effects”—distortion of inflation data that occurs when comparing current numbers to very high or low numbers from a year ago— are expected to continue for the next several months. Economists also expect base effects to reemerge in 2022 when comparing the early months of the year to the same months of 2021.

The final assumption by those who believe that the current inflation is temporary is that unemployment, which held steady at 5.9% in June, is artificially inflated because the $300 weekly federal unemployment supplement (in addition to state unemployment benefits) is incentivizing people not to work. Referring to reports of employers unable to fill open positions, proponents of this theory call for an end to the supplement payments, claiming many workers receive more in government aid than they would get on the job. Others say the payments have helped many lower-income families, who have disproportionately lost jobs in the coronavirus pandemic, while also pushing money back into the broader economy. However, some surveys suggest other factors keep people from returning to work, such as fear of contracting COVID-19 or lack of childcare. The federal unemployment supplement payments end after Labor Day.

Towneley’s View

We are in the “inflation is transitory” camp. We agree that recent supply disruptions are temporary and that base effects are contributing to short-term inflation anxiety. Another factor supporting our view that current inflation is just passing through is the ten-year US Treasury yield, which declined from 1.7% in May to 1.3%, despite rising inflation. The decline suggests that bond investors are not expecting current inflation levels to continue.

Second, with the rise of eCommerce, particularly during the COVID-19 lockdown, consumers can efficiently comparison shop online while visiting a brick-and-mortar retailer by asking if the retailer will match or beat a lower online price. This practice, called “showrooming,” is one example of how online merchants and technology have put downward pressure on retail prices.

Similar to the practice of showrooming, the global economy enables US manufacturers to shop globally for parts, supplies or facilities, or to outsource production to a foreign company in a country with lower wages, which promotes competitive pricing. Unfortunately, while this practice theoretically lowers production costs, it also puts downward pressure on wages.

Finally, we also believe that unemployment may decline somewhat once the federal unemployment supplement payments end. Still, the availability and cost of childcare, along with continued uncertainty about COVID variants and vaccines, and other factors, will continue to keep some formerly employed persons out of the workforce.

How Has Towneley Positioned Client Portfolios for Inflation?

In client portfolios, we have maintained a higher allocation to short-term bonds, which are less impacted by rising inflation than are longer-term bonds. Most client portfolios also contain Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) exposure, including short-term TIPS. The Vanguard Short-Term Inflation Protected Index Fund Admiral Shares is one of the best performing bond funds in client portfolios this year. The short-term TIPS fund has a higher correlation with inflation, so we expect this fund to do well if inflation increases.

When we fully rebalanced client portfolios this past February, we restored equity targets and brought clients whose gold exposure had fallen below 5% back to target. With TIPS, domestic and international equities, and gold all hedging inflation, we believe client portfolios are well -positioned for inflation at this point. As always, we continue to monitor the markets and the economy and evaluate opportunities as they arise.

So that we can continue to give you the best service possible, please notify your portfolio manager promptly if you experience any change in income, expenditures, health, family or other matters.