Modern Monetary Theory: The Cure What Ails the U.S.

As we head into the final quarter of 2019, we do so with some concern about recent fiscal and monetary policies being employed in the U.S. We discuss the potential pitfalls of Modern Monetary Theory in our Third Quarter Commentary that accompanies this letter. On a positive note, volatility in the domestic equity market (as represented by the CBOE Volatility Index VIX) is currently more than 40% below its overall long-term average, and below its 29-year historical average for the month of October. However, with a great deal of economic uncertainty continuing to spook investors, we expect market volatility to rise as new information about issues such as the U.S.’s trade war with China and the Fed’s next move on interest rates, is revealed.

The Economy and Financial Markets: Third Quarter Highlights

Domestic economic growth remains positive with a third quarter projection of 1-2%.

Low unemployment has kept consumers in the spending game, although income growth is rising at a slower rate than during past recoveries.

GDP, employment, and inflation all fall within the Fed’s suggested mandate, but Chairman Powell continues to promote easing.

After giving investors a rollercoaster ride this summer, the U.S. stock market seems to have settled down in October, historically the most volatile month of the year. Although the S&P 500 is close to its all-time high, it is fluctuating within a relatively narrow margin.

Developed and emerging market equities posted negative third quarter returns despite a strong September bounce due to positive trade news.

Domestic equities overwhelmingly outperformed international equities over the past year, as they have during most of the past 10 years.

Longer term bonds (governments and corporates) with maturities of 10 years or more have produced excellent returns over the past 40 years, and 2019 has been no exception. However, it is highly unlikely that long bonds will generate similar returns going forward, unless the Fed joins Japan, Europe and three other central banks, and sets rates below zero.

The U.S. government deficit is projected to exceed $1 Trillion in each of the next four years, while cash-flush companies’ buyback close to $1 Trillion in publicly traded stock. The potential fallout from this unbridled use of modern monetary theory tools inspired this quarter’s commentary.

Modern Monetary Theory: The Cure for What Ails the U.S.?

By: Martin Standish, M.B.A., CFA, CFP, CAIA

Modern monetary theory (MMT) has recently gained prominence given the ineffectiveness of recent monetary policies to adequately address economic shortfalls, such as lower than expect GDP growth. The central idea of MMT is that governments which control their own currency and borrow in that currency should print (or create with digital capabilities) as much money as needed in excess of revenues because they cannot default on their own debt. The resulting negative balance is called the National Deficit[1]. Spend it while you can create it and ignore the deficits, seems to be MMT proponents’ mantra. MMT proposes that spending be sustained until substantial inflationary risk emerges, at which point tax strategies can be implemented to curb consumer demand. Taxation is not only an inflation adjustment tool but can also be used as a tool to reduce supply, and thus increase demand, for the country’s currency.

Traditional monetary theory proposes that government spending that consistently exceeds revenues (i.e. deficit spending) would eventually lead to inflation and that targeting interest rates along with adjustments to money supply are necessary tools to maintain price stability. The U.S. has been financing its deficit with new debt for years and the Fed’s QE policy is a form of monetization intended to create more reserves to stimulate the economy, not to finance government spending. During this economic cycle, the Fed’s balance sheet has increased, decreased, and is now increasing again, but inflation has yet to budge. Modern monetary theorists argue that the national deficit represents dollars the government has put into the economy and has yet to retrieve through higher taxes, and so is not a precursor to inflation. MMT also holds that maintaining a large government deficit will not lead to economic collapse, so large developed economies like the U.S.’ can sustain increasingly larger annual deficits.

The U.S. fiscal year-end closed September 30 with an estimated annual deficit of $980 billion, while the 2020 fiscal year budget estimates annual deficits exceeding $1T in each of the next three years. MMT advocates believe that if rising deficits are not sparking excessive inflation, then why not keep spending? The reason is socio-economic: the rising U.S. deficit is indirectly contributing to growing income inequality in this country. As the wealthy get wealthier, they are less likely to spend more, but they will invest. During the past decade, government-induced income streams have been driving policy may be impossible to sustain if GDP growth cannot generate enough revenue to service the National Debt.

Case in point - Japan

Japan has run fiscal deficits for decades with mixed results. Since Japan’s economic boom burst in the early 1990’s, the government has borrowed heavily; and its debt is now approaching 250% of GDP, although recent forecasts suggest it may stabilize around 230%. Critics regularly point out that continual deficit spending has done little to boost Japan’s GDP growth. Despite Japan’s asset prices (stocks, bonds and real estate) higher.

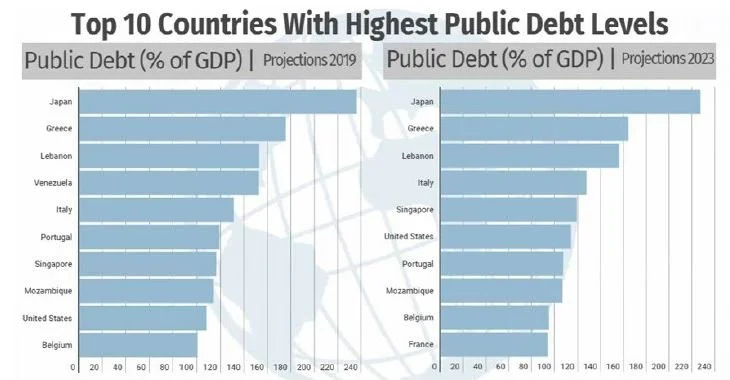

Countries with most public debt

Source: Focus Economics

Some politicians and advocates believe the government should spend more on programs and services that benefit the middle and lower classes which would fuel consumer demand, increase prices, and result in inflation. At some point, however, as the annual deficit grows larger relative to GDP, the “helicopter money[2]” economic shortcomings, domestic inflation and lending rates remain low and government debt trades at negative yields, enabling Japan to profit from borrowing money. Despite having the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the developed world, Japan remains an economic powerhouse (3rd largest economy in the world) with a well-above-average standard of living.

Japan’s current MMT policies evolved in two waves. The first wave occurred after Japan’s economic bubble burst in the 1980’s and huge spending programs were implemented to drive recovery. The second wave began in 2012 when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe implemented his Abenomics plan which called for massive spending on public projects coupled with loose monetary policy. Abe has pledged to find ways to pay down Japan’s now insurmountable debt. However, many believe his most recent effort--increasing consumption taxes from 8% to 10%--will stall the economy, as did his previous tax increases.

The typical monetary and fiscal policies used to reduce public debt are, unfortunately, unlikely to help Japan:

Economic Growth - This is a difficult task given a shrinking population and stagnant economic growth rates. Although the Japanese economy grew slightly in 2017 and 2018, the tax increase and trade war pose new obstacles.

Repayment - This would require budget surpluses over many years despite the large spending required for its aging population. Abe has indicated the upcoming tax increase is unavoidable given the demographic challenges. Japan’s very ambitious goal is to be more fiscally responsible and balance the budget by 2025.

Default - This is not a viable option as the majority of all the debt is owned by the Bank of Japan and Japan’s internal domestic financial system (pensions, banks, insurance companies, etc.).

Inflation - Japan has been unable to stimulate inflation for decades and higher prices now would distress its savings-focused citizenry.

Recently, Japan’s central bank held a 10-year bond auction, and no one showed up, which made waves around the globe. The usual buyers, other central banks and pension funds balked following announcements that the Bank of Japan intends to buy fewer bonds in October, and that Japan’s largest pension fund is considering investing in currency-hedged foreign debt. Following these announcements and Japan’s botched bond auction, bond yields rose abruptly in Japan, Europe, and the US bond markets. What happened in Japan can happen in other countries that deficit spend to the point of creating central bank illiquidity. Further, the impact of the Bank of Japan’s actions was not limited to the Japanese bond markets; it had global repercussions. While the U.S. economic deficit, now at 103.60% of GDP (Q2 2019 Fed Reserve Bank of St. Louis), isn’t as large as Japan’s, no buffers are in place to stop its ascent.

What about the U.S.?

Could what’s happening in Japan happen in the U.S.? Yes, if our government does not take steps to slow our growing deficit. Like Japan, the U.S. has racked up a massive deficit since the 2008 global financial crisis. The longest bull market in Wall Street’s history which began in March 2009, has been fueled by low interest rates and quantitative easing experiments which encouraged corporations to buy back shares (approximately $800B in buybacks in 2018 and approaching $1 trillion in 2019).

Historically, the U.S. did not intentionally engage in open-ended deficit spending during a time of economic growth. The following chart, however, suggests that we may be heading for trouble at the rate we are currently outspending GDP:

Some believe that radical MMT spending targeting investments in education, infrastructure, and research & development just might bring longer term benefits for the economy and financial markets. Positive outcomes may result if global investors still favor U.S. debt, and the Fed has an arsenal of escape policies at the ready in case, as occurred in Japan, the bond and/or stock markets turn on a dime. But are the potential positive outcomes worth these risks posed by MMT? The risks include:

Hyperinflation

Currency devaluation

Fiscal irresponsibility

Crowding out of private investment

Reliance on tax cuts and spending cuts to quell inflation, which isn’t very popular from a political perspective, and

Unchecked deficit spending which contributes to an ever-increasing ratio of debt to GDP, the consequences of which will eventually be borne by future generations.

Politicizing monetary policy by placing control of the money supply in the hands of professional politicians.

During times of uncertainty that often occur late in the business cycle, new and unconventional economic theories may be embraced in hopes they will move us through the inevitable downturn ahead faster and easier. We humans are an impatient bunch, we want the quick, easy fix. But sometimes the cure is worse than the disease. And that looks to be the case with MMT.

[1] The National Debt is the debt the federal government owes to the public, intra-governmental agencies, the Federal Reserve and foreign investors. The National Debt rises when the government borrows to reduce the National Deficit.

[2] “Helicopter money is a theoretical and unorthodox monetary policy tool that central banks use to stimulate economies. Economist Milton Friedman introduced the framework for helicopter money in 1969, but former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke popularized it in 2002. This policy should theoretically be used in a low-interest-rate environment when an economy's growth remains weak. Helicopter money involves the central bank or central government supplying large amounts of money to the public, as if the money was being distributed or scattered from a helicopter.”

Quotation from: What Is the Difference Between Helicopter Money and QE? By Steven Nicholas, Investopedia, Updated Oct 17, 2018, retrieved October 11, 2019. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/082216/what-difference-between-helicopter-money-and-qe.asp